The ‘New Silk Road’ will consist of roads, railways, ports, pipelines and fibre-optic cables linking China with Central Asia, the Middle East and, eventually, Europe and Latin America.

Like its legendary predecessor, the network consists of both a land and a maritime route. The logistics of developing it are immensely challenging. What could Australian humanities researchers possibly contribute?

Plenty, says Brett Neilson, research director of Western Sydney University’s Institute for Culture and Society.

Together with international collaborators, he is investigating the cultural and social impacts of the mega-project on communities along its route, where Chinese investment is transforming the way people work and live.

While technical and managerial expertise are critical, says Neilson, so is the capacity to navigate differences in language, culture and labour practices, along with social and political complexities.

Although much of the attention generated by the New Silk Road has focused on new and upgraded road and rail links, infrastructure is just one element of logistics, according to Professor Neilson. He is studying three key container ports: Piraeus in Greece, Kolkata in India and Valparaiso in Chile.

Logisticians seek the most efficient means of transporting people and goods—and, increasingly, ideas and technologies. While technical and managerial expertise are critical, says Neilson, so is the capacity to navigate differences in language, culture and labour practices, along with social and political complexities.

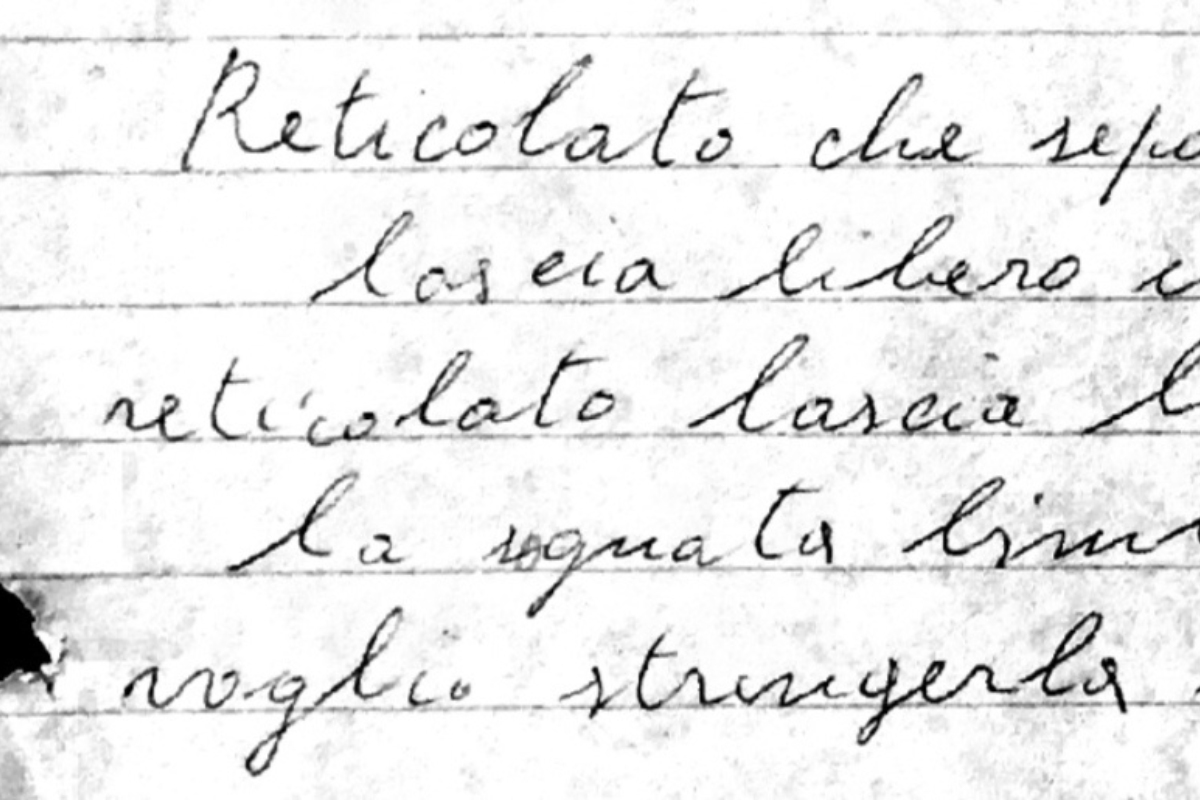

That is sharply evident in Piraeus, where part of the port has been leased by China’s state-owned shipping company, Cosco. The remainder is still owned and run by the debt-strapped Greek state, with a chain-link fence separating the two workforces.

The unionised dockers on the Greek side are suspicious of the non-unionised, more modern and more productive Chinese operation. The stevedores’ union managed to stir up a brief strike on the Chinese side in 2014.

Outside the port, China has built a new rail line linking Piraeus with a logistics centre under construction on the outskirts of Athens, from which Chinese goods will travel on to European markets. Some of the railway fencing has been torn up and sold for scrap metal by low-income families living in the hills outside Piraeus.

Wider cultural and political factors are at play in the anti-Chinese sentiment which the New Silk Road arouses in some quarters, where it is viewed as a front for Chinese global military ambitions.

For Australia, the new trade corridors present lucrative opportunities but also challenges, such as enhanced competition from Chile, a rival supplier of raw materials to China. Also significant for Australia will be the effect of massive Chinese investment on developing nations in its region.

Neilson collaborates with industry and other key logistics players through a Sydney think-tank, the Future Logistics Living Lab.

Closer ties with Asia are crucial if Australia is to take advantage of its position in the region in coming years. Neilson believes his study will deliver vital insights for companies and policymakers.